In Her Own Words

Grace Ellen Miller

|

Grace Ellen Miller was born July 24, 1889 near Rantoul, in Franklin County, Kansas as the fifth child of Sylvester Miller and Anna Louisa Williams. After four sons, Grace was the much loved only daughter of the family. Two more sons were born after her. She had six brothers, namely: William Penn, Franklin Blaine, Frederick Everett, Robert Dewalt, Vernon Harrison, and Henry Thomas.

|

Grace Ellen Miller about 1915, around age of 26.

|

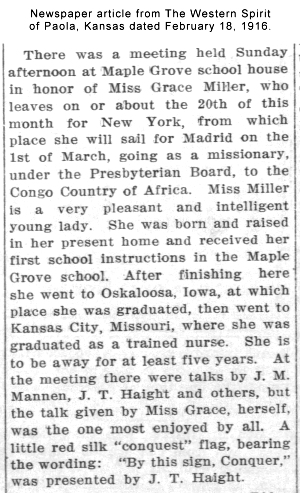

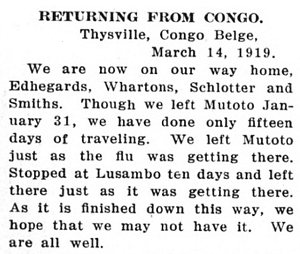

Newspaper article from The Western Spirit

of Paola, Kansas printed February 18, 1916.

|

Grace grew up on the family farm where her parents raised horses, cattle, hogs, and chicken among other animals. Her father was a beekeeper, grew corn, oats and various crops. Anna and the children helped to grow many fruits and vegetables for their own table in their large family garden. The boys were expected to work hard out in the fields and around on the farm with their father.

One-quarter mile from their house, she attended the 18x24 foot, one room, Maple Grove school that paid one teacher to teach grades 1 through 8. When she finished eighth grade, she went to school in Wellsville, beginning fall of 1904, at the age of 15.

|

Years later in a letter to Debbie Owen dated March 12, 1983, Henry described his older sister as "brown eyed like her mother, rosy cheeked, with heavy dark brown hair, in long braids. Grace was vigorous, full breasted when grown... Grace was always loving and agreeable, playful."

|

Anna encouraged all of their children to get a good education with the hopes of greater work opportunities. In the fall of 1905, Grace went to business school in Ottawa, Kansas. In May 1906 she graduated from the county high school. During the summer of 1906, Grace worked as a stenographer and typist in Kansas City, then in the fall attended the teachers training at Kansas State Normal School in Emporia, Kansas, about 85 miles from the Miller home. Grace was 17 years old.

Then Grace attended nurses training at Kansas City Hospital, Missouri but returned home after two years when she grew disgusted with the moral standards of those in training, according to Henry.

|

Grace Ellen Miller about 1910, around age of 21.

|

And so, Grace found herself back home in her late teens, without a firm direction in her life.

Henry goes on to say in his letter,

"When our brother Frank took up with some radical religionists who told us we were lacking unless we were sanctified, Grace tried to have the experience, shut herself in her room saying she would not come out till she had the experience."

This seems to have changed her direction. She attended classes at Central Holiness University near Oskaloosa, Iowa, where she used her secretarial training and worked in their school office to pay her costs.

Central Holiness University about 1910.

|

The next fall, Anna and Grace convinced her youngest brother Henry, to enroll in Central Holiness University also, with the intention to get him off of the farm and away from a girl that wished to marry Henry. Together they rented a one room house where Grace did the cooking. Henry worked odd jobs while Grace continued her job at the school office to pay their rent and tuition.

|

At the end of the year at Central Holiness,

Grace heard about the American Presbyterian Congo Mission and their need for doctors and nurses on their mission field in Africa. She decided to return to nursing school at Kansas City Hospital, Missouri to become a medical missionary. She completed her training in December 1915.

|

|

|

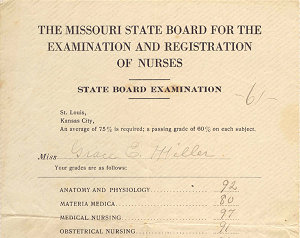

Registered Nurse Examination undated, but possibly from December 1915, since a farwell party for Grace was announced in her local newpaper on January 28, 1916.

|

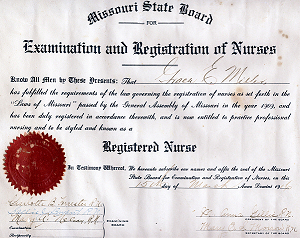

Dated March 15, 1916, the certificate for Registered Nurse was issued to Grace E. Miller after she had already boarded a ship to Africa.

|

On February 20, 1916, Grace departed Rantoul, Kansas to begin her journey to Africa.

Following are articles from various publications which were written by Grace describing her trip and her work in the Congo region. At first she was just writing home to her friends and family, but when her mother Anna took the first letters to their local newspaper, The Miami Republican of Paola, Kansas, the editor printed them and the readers made it known that they loved it. The editor mailed free issues to the Miller family and to Grace in Africa in exchange for the letters.

Other newspapers such as The Western Spirit of Paola, Kansas and Capper's Weekly of Topeka, Kansas also printed a few articles on the subject.

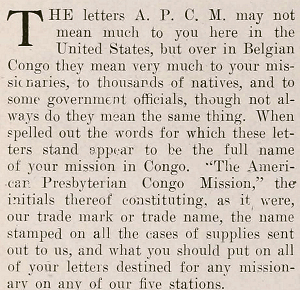

The American Presbyterian Congo Mission asked their missionaries to write articles about their work in the mission field for publication in their own news, The Missionary Survey and The Presbyterian of the South.

Grace wrote most of the following articles. Sixten Edhegard wrote one article which has two versions. Grace most likely helped him with it, since English was his second language. Other articles that were written for the American Presbyterian Congo Mission by various missionaries that knew Grace and Sixten are also included below to give insight into their situation.

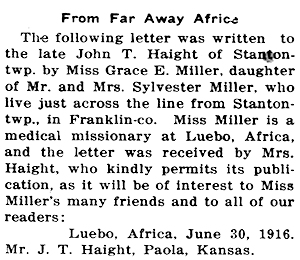

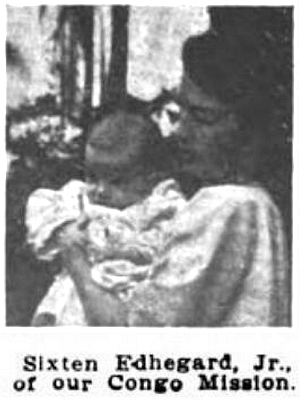

From Far Away Africa

Written by Grace E. Miller

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed September 15, 1916.

|

The following letter was written to

the late John T. Haight of Stanton-twp.

by Miss Grace E. Miller, daughter

of Mr. and Mrs. Sylvester Miller, who

live just across the line from Stanton-twp.,

in Franklin-co. Miss Miller is a

medical missionary at Luebo, Africa,

and the letter was received by Mrs.

Haight, who kindly permits its publication,

as it will be of interest to Miss

Miller's many friends and to all of our

readers:

Luebo, Africa, June 30, 1916.

Mr. J. T. Haight, Paola, Kansas.

|

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed September 15, 1916. - Click to see entire article.

|

My Dear Friend:

I have thought

for some time of writing you a short

letter to let you know of our trip and

safe arrival in the fair land of Africa.

We were delayed some time in New

York. The steamer in which we were

to sail was delayed in sailing several

days. During that time we received

a message from our mission board forbidding

us to sail on the Roma on account

of war conditions. We finally

succeeded in getting passage on a

Spanish steamer. We sailed from

New York on the tenth day of March (1916).

We were very glad to start after so

many days of waiting and uncertainty.

A few hours, however, changed the

smiles of our party and most of the

other passengers to a more serious

look. Sea sickness! It must be experienced

to be described. Even the

three little ones in the party were sick.

I would have enjoyed going to bed, but

with everyone else sick I really did

not have time. We all survived, however.

I enjoyed the voyage to Cadiz, Spain.

Nothing of importance occurred except

being held up for inspection by a

French vessel. We arrived in Spain

on the 22d day of March.

Cadiz is an ancient city. We were

told it was founded before Rome. The

little narrow streets are quite puzzling,

especially when you cling to the

side of a building to escape the passing

donkey cart. Yes, they are that

narrow, and the sidewalks are wide

enough for just one person.

We were in Cadiz a little over a

day but we tried to see as much as

possible. We visited a museum (we

would call it an art gallery) and saw

some of the paintings of famous artists.

They were really wonderful. The

catacombs in one of the Catholic cathedrals

were especially interesting to

me. Far down in the basement we

saw the rooms for imprisoning those

who needed punishment. In the center

of one large apartment any sound

set in motion, shall I say echo? came

back thirty times. I thought it would

be a good place to sing.

We enjoyed our few days' journey

from Cadiz to the Canaries. We

reached there on Monday, March 27,

and went on shore in the Gran Canaria

Las Palmas. Fortunately we were

here only one day, as we secured passage

on a Portuguese steamer en route

for Loanda, Africa. The water around

the Gran Canaria is the most beautiful

I had ever seen! It is deep blue

until it rolls toward tbe shore, then it

changes into all kinds of beautiful

colors.

After we left the island we ran several nights without lights on account

of the dangers of war. We were so

glad when we were through that part

of the war zone. We crossed the

equator without any serious difficulty.

We were delayed several days at St.

Thome because of cargo to be unloaded. This island is noted for its cocoa

farms. The water about a mile from

the shore is even more beautiful

that at the Canaries. We could stand

on deck and see the bottom of the

ocean and hundreds of fish. The men

of the ship spent many hours fishing,

but with little success. So many

needle fish interfered with the catching of the larger fish.

We reached Loanda on the 14th of April. We were delayed here one week. It was really quite warm here, much warmer than at any place farther inland.

We were glad to leave Loanda, although time did not drag even here. I visited the hospital and was surprised to find such a large and well equiped institution. the prison, with its many, many prisoners, both men and

women, made me realize more than

ever the awful effects of sin upon humanity.

We left Loanda on the 21st

and reached Boma the next day. We

were here three days, then went on a

launch to Matodi, a day's journey.

From Matodi, after a night's rest, we

went on a little railroad. The train is

not very modern and not very attractive,

but it brought us safely to Hyceville,

where we spent the night. The

train does not run during the night.

We continued on our journey the next

day and reached Leopoldville in safety.

Here we found our mission steamer

waiting to take us up the river and to

our station. We left the next morning

and reached Luebo on the 12th day

of May, just two months and two days

from the time we left New York.

How glad we were to reach our destination! How glad everyone seemed to

see us. God has truly guided us in

safety and kept us from the dangers

which were hidden from our sight.

We are busy now. I shall not try

to tell you of our work in this letter,

as it is bed time. Give my best regards to all. Will you let Sarah Alice

read this, as I have so many things to

do I do not know when I shall find

time to answer her most welcome letter.

Sincerely,

Grace E. Miller.

(My native name:)

Mama Mukuacisa.

Another Letter From Miss Miller

Written by Grace E. Miller

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed September 22, 1916.

|

Miss Grace E. Miller, who is a medical missionary at Luebo, Africa, has

written another letter to her parents,

Mr. and Mrs. Sylvester Miller of

Franklin-co., near Stanton in this

county, from which we take the following

extracts:

|

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed September 22, 1916. - Click to see entire article.

|

Luebo, Africa, June 30, 1916.

Dear Ones in America:

I suppose you cannot realize that

Africa is much like home. To-day we

had a real rain. It was cold and was

so dark at 1 o'clock that I had to light

a candle to study my lessons by. We

were very glad of the rain, as it had

been several weeks since we had one.

Miss F. will probably leave in two

weeks for America. Of course these

war times are times of uncertainty. I

am enclosing you a paper, but am sorry

the ants ate part of it. Dr. C.'s

baby is yet sick and the poor little fellow

does not seem to improve much.

The Doctor is all run down and nervous. (This was Dr. Llewellyn Coppedge.)

Well, I stop so many times and begin

again that I hardly know what to write.

I have been sending you letters on the

average of one per week, so notice if

you receive them all. I am sorry I

did not bring more table cloths, dish

towels, dishes, tea towels and such

things. I think of you all so often and

almost know you are not far away. I

am longing so to be able to talk to

these people. I am getting along fairly

well with the dialect. Probably by

the time I get home I'll be speaking it

more fluently than English. We have

plenty to eat, but are nearly out of

flour and are low on sugar and oil. We

burn candles almost entirely, so the

scarcity of oil will not worry us very much. I am feeling quite well, sleep

well, work some, study some and

think some. Just received a letter

frome home. Was so glad to get it,

also one from brother H. in Iowa. Your

letters were mailed the 6th of April

and this is June 30, but I feel I have

direct word from you by way of the

throne.

Thank you so much for taking so

much trouble with the grades. You

need not bother sending my diploma.

I passed any way. I enjoyed your letters.

So N. is married. I wish them

happiness.

I Would like to help with the farm

work and am looking forward to several

months with you all at home in a

few short years. I'd love to peep in

just now. I suppose you are just eating dinner

and we are ready for supper. We are not operating these days and I am glad, for I need all the time

I can get for my studies. The surgeon is still away. The sunrises and sunsets

are so very beautiful here. The

moonlight is wonderful, also. One

can almost see to read by the moon's

light. We have very nice native boys

and are all willing to work. We do

not have to work hard, for we are here

to teach and help them to learn to

work. These people are quick to understand

and respond readily. They

certainly enjoy learning. You may

ask as many questions about conditions

here as you like. I almost know

there are things I forget to mention

you would like to know.

Pray for the natives here. They

suffer much persecution from the Belgian

government. It is terrible the

way they are caught and forced into

Belgian service.

May God bless and help you. Love

to grandma and grandpa and much

love to you all.

My new name is Mukaucixa. We

pronounce it Moo-qua-chee-sa.

Lovingly yours,

G. E. M.

From Miss Grace Miller

Written by Grace E. Miller

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed October 6, 1916.

|

Luebo, Africa, July 18, 1916.

Dear Ones at Home.

|

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed October 6, 1916. - Click to see entire article.

|

I have decided that I must take a

few minutes and write to you, for if I wait until I am not busy, then a

steamer might come and I would have

no letter to send you. I am well, but

I get very hungry to see you all. Some

day we won't be scattered over so

much territory, I hope. Miss F. is on

her way to America now. I suppose

by the time you receive this she will

be in America. Excuse the way I am

rambling over this paper, but I seem

to find no blotter, so write this way to

keep from blotting. We are having

very cool weather here now, and it is

very damp. Will be glad when the

rainy season comes, I think, for they

say it is more pleasant then. One of

our missionaries bas fever this morning.

It usually lasts two or three

days, when plenty of quinine is given.

Ten grains at once almost takes me off

my feet. The doctor is coming this

week. I have never seen him, but

they say he has red hair. Dr. C. is no

surgeon, so our operations are small

at present. Am so anxious for Dr. K.

and wife to come. At present I am at

a disadvantage to teach my boys and

girls, not being able to talk much so

they can understand. I will be so

glad when I show some signs of intelligence.

Ha! ha!

Next Monday is my birthday. Would

love to spend it with you. Have not

heard from Bessie in India since I

came to the Congo. Probably we will

have some difficulty in hearing from

each other. I told you in a previous

letter that we stay only three years

before we get a furlough. For fear

you did not receive that letter I will

repeat it again, as letters are very uncertain now. We have the nicest pawpaws here. They are something like

muskmelons, only better, also have

egg plants and bananas. I wish you

could have a bunch of the bananas.

We do not suffer for food, although

we have very little flour left at the

station. Of course we can get along

very well for awhile.

We had 195 at Sunday school, that

is, boys up to the age of 12 or 14 years

old. The natives do the teaching.

We have only five teachers for that

number and one of the teachers was

absent last Sunday.

Ethel, how do you like farming?

Have you learned to ride horses and

milk the cows? Does your dog keep

you plenty of company? Be careful how you hitch him to a sled when

there is snow on the ground; you

might get another fall. Did you have

plenty of mulberries this year? I almost forgot about the strawberries and

cherries. Hope the cold weather did

not catch them.

Did I ever tell you

how large our home is? Six rooms.

Think of it, I almost feel lost in it.

The kitchen is separate from the house

proper. The house is made of mud,

dirt floors, with mats to cover it.

This is July 21. Well, you see time

goes in the Congo as in America. We

live and move and work. It is five

months since I left home to come

here. We had some rain last night.

Give all the folks my love and tell

them I think of them often. The other day I met two little boys who had

a big beetle, which they wanted to sell

to me. This would be a capital place

to collect bugs. Brother Henry, I

wish you could have a chance at them.

They are all over the bouse and outside, and anywhere you might look you could see bugs.

Well, I must think about saying adieu.

With much love to you all I think of you and will you pray for me, that I may accomplish the work that He has given me to do. May the love of the Savior abide with you forever.

Grace Miller.

P. S. - I wish to thank the sisters of Spring Ridge and Stanton for the liberal and prompt response made for table linen, etc., and the many good wishes and words of cheer accompanying them. I am sure the Lord will bless each donor, for we have His propise that no gift however small goes unnoticed by our heavenly father. Again thanking you for your generosity and kindness, I am, yours truly, Grace's Mother.

In Far Away Africa

Written by Grace E. Miller

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed October 27, 1916.

|

The following letter is from Miss Grace Miller, a medical missionary in Africa, written to her parents, Mr. and Mrs. Sylvester Miller, of near Stanton:

Luebo, Africa, July 29, 1916.

My Dear Ones:

|

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed October 27, 1916. - Click to see entire article.

|

I think it is time

to write you a letter, although I have

just sent one. However, we are expecting

a steamer and I want to have

a letter ready then. I am hoping to

receive a letter from you, for I have

had only one since my arrival here.

Well, I had a birthday last Wednesday

and we went on a picnic to the

river. We were gone about three

hours, so you see how long our picnics

last here. (Grace was 27.)

Just received your good

long letter, so glad to get it; one from

brother Henry, one from one of the

girls at the hospital at Kansas City,

one from Bessie in India, written some

days before yours and two Christian

Heralds.

Do you ask if I ever get

lonesome? Well, you know how it is

to be busy, so you have no time to

think about it. That is the way with

me.

We have had a very sick woman

this week. She is nearly ready to

leave now. We had little hope for

her recovery and feel it is a great victory,

as they had tried their native

medicines and failed. We feel grateful

to the Lord for her recovery, as it will

probably mean much. I took her little

baby to the village this evening, to

find a woman to give it nourishment.

I found a very nice woman, who was

glad to help in time of trouble.

The

native houses are not very large,

usually one room without windows and

one door just large enough to walk in

by stooping. A mat on the floor and

a few cooking pots and some fire wood

is about all you see in the way of furniture.

The people have such a hard time

under the Belgian government. The

natives are all taxed, and if they are

not able to pay, they are captured for

soldiers. One of our women came to

us to-day crying, saying, "they have

taken my husband." I felt so sorry

for her, but we can do nothing about

things like that. It is very hard to

understand such things. One would

think that when they had suffered so

much in Belgium that they would deal

mercifully with these poor people, but

they treat them like brutes. They

throw them in prison and chain them

together. Some times epidemics of

fever break out, and in the morning

one may awake and find the prisoner

to whom he is chained lying beside

him dead, and he does not know how

long he will have to stay chained to

him. It is horrible to think of and the

natives have such a fear of the dead.

We have a patient here who is so poor

you can see each rib as far as from

our house to the barn at home. Truly

you can, and almost count them.

Money is the last thing a person in

America should send to Africa. It

would be a very difficult matter to send

it, anyway. We have very little use for

any, except what comes through

the office, because there is nothing

much to buy. The time when we will

think of money will be about two and

one half years from now, when we land

in New York City, with just enough

clothes to get to a dry goods store, just

enough teeth to give the dentist a

foundation to build on, and just enough

hair to need a wig. Nonsense, I shall

have enough uniforms to wear home,

unless I need shoes to appear in

America and my teeth are as sound

as dollars, but I sure miss toothpicks.

Now, thank you for the poetry, and I

appreciate every bit, too. Thank

Louise for the flower. It was not

broken one bit. I would love to see

all my little nieces and nephews. Give

them all a hug for me and tell them

I'm coming to see them some day. If

Jesus comes before I get there, we

shall just go to heaven and see each

other and I would be saved the

trouble of being sea sick. I would

love to run up and see Grandpa and

Grandma; give them my love.

Our rainy season will begin in almost

a month and then I hope to have

a garden and raise some lettuce and

cucumbers. I'd give a fabulous sum

for your cow and almost any price for

a stand of bees. It does seem so bad

not to have horses to work and no coal

to run engines with and no machines.

I would almost be rejoiced to see even

an old Western washer. We do not

have to wash, but I'd like to see them

wash some other way than pounding

them on a board or table. It wastes

so much water and soap to bunch up

the clothes and pound with them.

However, they look very well. I'm

afraid I don't write what interests you.

We had some pictures taken, but they

were no good. I was so sorry, for I

knew you'd like to see the new hospital.

I am feeling very well except

a dreadfully sore toe. You see, when

you read this letter it will be entirely

well.

We have such nice pineapples

now. I just wish I could send you

some, but you know one of the things

I miss most is going down cellar and

getting a can of fruit. Say, those

cherries sound well, but come to think

of it they are all gone, are they not?

I shot a hole in the wall, but did not

kill my rat. The rats are pretty bad,

so I am anxious to get my cat.

One tribe of natives near Luebo

makes cloth, but it is so very coarse

and stiff that they soften it by beating

it, and that makes it full of holes,

which must be mended.

Our hospital

cases are doing well. They sat up today

and looked so happy. A couple of

hours later I went back in the ward

and they were still sitting up. I told

them they should go to bed for awhile.

They acted as though they thought

now they were up they had to stay up.

They went to bed and each of them

seemed as though the bed was the

nicest place in the world. The women

carry water over a mile up hill, too.

My alarm clock is a great comfort to

me. I'd give $5 if it would just start

striking. Next time I come to Africa

I want a noisy one.

The boat is leaving

in the morning, so this will soon

be on the way. Jesus is an ever present

help. What a dreary thing life

would be without Him. May His

blessing abide with you. M., you and

E. must take good care of father and

mother.

Yours in Africa,

G. E. Miller.

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed December 1, 1916:

|

Mr. and Mrs. Sylvestver Miller are in

receipt of letters from their daughter,

Miss Grace Miller, who is a medical

missionary in Africa, dated September

2 and October 5, advising them of her

continued good health. She is working in the operating room, enjoying the work, but wishing to see home folks. The weather was quite warm and they planted flower seed, etc. They had buried one of the mission children.

|

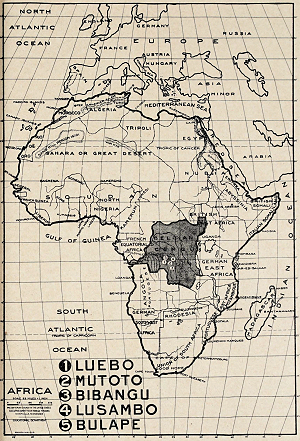

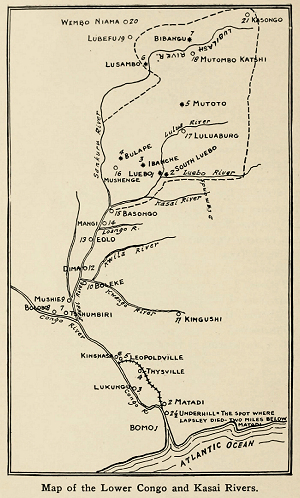

1917 Map of Africa. - Click to see larger image.

|

From Miss Miller in Africa

Written by Grace E. Miller

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed January 5, 1917.

|

Mr. and Mrs. Sylvester Miller of

Rantoul are in receipt of another very

interesting letter from their daughter,

Miss Grace Miller, a medical missionary

in Africa, which we are permitted

to publish. Mrs. Miller asks that

those of our subscribers who would

like to read more of these letters send

her a postal card, which we believe

many will do, as the letters are very

interesting. The letter follows:

|

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed January 5, 1917. - Click to see entire article.

|

Belgian Congo, Central Africa, Oct. 18. 1916.

My Dear Ones at Home:

It has

been some time since you have bad a

letter from me. I am sorry, but I did

not have one ready when the boat

left. However, you may get this one

as soon as you would have another

sent several weeks ago. You see we

can start a letter from here, but we

have no way of telling how long it

will wait before it finds a steamer

from Africa.

Just received word a

little while ago that we could send

mail this evening, so I take this opportunity

of writing a few lines, as it

will reach a boat that is going to

Europe, and you may receive it before

Christmas. I wish you all a very, very

happy Christmas. We will think often

of you and almost wish we could step

in and bring you over here with us,

but of course that can not be.

We

will be having some warm weather at

Christmas time, as they say it begins

to be very warm about then. At the

present we do not mind the heat very

much unless it is necessary to be out

in the sunshine in the middle of the

day.

We have had the care of another

little missionary since my last letter to you. He is a fine little fellow

and is doing nicely. He is not quite

two weeks old, but we all think lots of

him. This makes the fourth little

missionary to arrive since I came to

Luebo, but two of them left us for

heaven shortly after coming here.

Well, I am glad to see in the Christian

Herald that war is a thing of the

past. I am glad, for it does seem

awful that the United States would

also be in that terrible business of

killing their fellowmen. I would

surely miss the Herald if it should quit

coming. I think every copy has come

safely through. It is the only paper

I receive. You know I am so sorry

that I did not have some little paper

like Dew Drop or Little Learners sent

me here, for I might be able to transate some of those little stories to my

little boys.

If you should ever think

of sending me money, just don't. Of

course if you should want to help the

missionary cause it is best to send

to the committee, but I meant personally. The best thing to do is to

order what you want and have it

shipped to me.

I think I will have to

order more shoes before my time is up

here. I am sorry, too, but of course I

would not like to go without them.

I will just include them in my next

order, or rather some of their other

orders.

Of course if I should decide

to get married I will probably have a

rather large order of my own to send

in. Nothing certain about it, as there

is no one here to marry, so there is

not much danger. I will give you

many, many warnings before such a

misfortune overtakes me in the heart

of the dark continent, but you see I

must indulge in some fancies, as

things go on much the same here and

you see the same people day after day

and eat the same things day after day

and do the same work day after day,

just like people all over the world, except

our climate is a little more depressing

than it would be if it would

snow a little once in awhile. We have

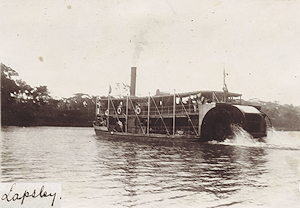

had a fine big rain and the Lapsley

has gone down the river to bring us

some more people.

|

|

River scene. Flodscen.

|

Lapsley. The river boat, Lapsley.

|

I am in the hospital

writing. Not a great many patients

now and I am glad for Dr---

left Sunday and I am sure I would not

know what to do if some great thing

should happen. He will probably be

gone a week yet and I'm trying to

hold down his part of the work.

I am pulling teeth, yes, honestly, I am.

This morning a woman came in and

wanted two double teeth pulled. Well,

they never wait for them to get loose,

but when they pain they want them

pulled. Well, my heart almost failed

me, but I said "come on." I had one

man hold her head and it took all the

strength I had to get one out, but out

it came. We had a good many waiting

for medicine, so we left her until

it quit bleeding and then went back

to her and finished the dental work.

She paid us with two eggs. You see

they must pay for their medicine, so

they are not beggars. They pay mostly with corn and the little shells which

they use for money. I must send you

some of these things some time. I

mean shells, not corn, as their corn is

much like ours at home only the ears

are not as large.

It looks like it might

rain again this evening. I would like

to plant some flower seeds, but it

seems I shall never get at it. Well, I

must hurry. I am not going to read

over this letter, so you had better correct

all mistakes before passing it on.

I had a nice long letter from Robert

and Velma, which I enjoyed very

much. I think I must be as glad to

hear trom you folks as you could possibly

be hearing from me.

Also enjoyed

the letter from sister Elma. Would be so glad to see them.

I think they should send me their pictures. Henry, you must let me know how you get along. I am so anxious to hear where you are in school. Would like to have a letter for you, but couldn't. It takes a letter nearly two months longer to reach me from India, where Bessie is, than it does from the U. S. A. Is not that unexpected? I had a letter from her last week and she had not heard from me.

Her letter was written in June and I

received it in October.

I am glad you

are all keeping well. How much I

would like to see you, I can not say

and will not try to tell you.

We are

going to have a new kitchen. I will

be very glad, as the one we have now

is so dark and you can not expect the

boy to keep it clean, because he can

not see to. You know they can not

realize about dirt, for they are so accustomed

to it. When they eat they all sit around on the ground together

and eat from one pot with their

fingers. They are very liberal and

will share the last thing they have.

They eat only twice a day. The little

boys will see their dog has something

to eat even though they go hungry

themselves.

I have not had a fever

and have been here a little over five

months. Well, I must say it's time to

stop. I am enjoying my work and am

leaving it with the Lord as to the

amount of good my presence in Africa

is doing. It sometimes seems that

you can accomplish very little, but

we must not expect wonderful things

to be brought about by little people.

With loads and loads of love to every

one, I remain,

Yours most affectionately,

Grace E. Miller.

Who will send me the address of

the papers that daughter mentions in

her letter, also how many of The Republican readers would mail me a

card requesting a continuance of her

letters being published in The Republican

and their appreciation of the

same.

Mrs. Anna L. Miller,

Rantoul, Kansas.

The following is a letter that Grace wrote to her family. It was not published, but only meant for the family.

Mr. & Mrs. S. Miller

Rantoul,

Kansas

U. S. of Am.

Luebo, Africa, April 1, 1917.

My Dear Ones:

Just a few lines to you this afternoon so as to send it in the morning. Two small steamers came in this morning but no mail. I think one leaves in the morning so I want to get a word to you with it. The other probably will not leave before Tuesday as I will have time to write a longer letter to send by that.

Dr. Coppedge was called away yesterday morning to see a state or company man who is sick. It is a day's journey with hammock men. We think he will probably return tomorrow evening.

|

|

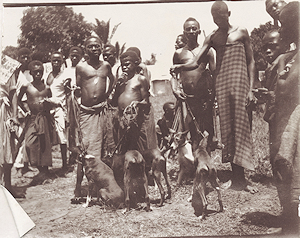

Scenes from the market Luebo. 1917

|

Scenes from the market Luebo. 1917

|

Dr. Coppedge removed my corns a few days ago and my feet are so sore. My only consolation is that I hope to have no more corns. Henry you spoke visiting my ward. You would have hard work making yourself see where it started and where it ended. We have a big shed where the men with sores stay. We have a good many bad ones at present. One little boy with the nails off of all the toes on one foot and swollen twice their natural size. One of the patients brought him home from the market. I must remember and tell you about the market in my letter tomorrow and I believe I have a picture of a little part of it.

View from Luebo. The hospital right. Jan 1917. Our first Congo home, Luebo, at left.

|

Then we have a small brick house where the women with sores stay. At present we have no women staying in the hospital who have sores. Then the main building really has two wards and a small ward between. Henry, you remember the Men's Ward at the General. The three altogether would make one about that size. At present it is all and more than we need. We have some cases of malaria but we soon finish them and send them home.

|

Everyone is fairly well. None of the missionaries been sick since I have been here. I have had a few headaches but no fevers. One of the little boys in my yard told me the other day when he knew my feet were sore that they would pray God to make them well. I have five in the fence now. Sixten took a picture and I want to send it to the Survey so perhaps you will see it there.

Well I will send this short letter in the morning for a few hours difference in starting a letter here may mean a difference of weeks in your receiving it.

With much love, Grace

From Africa

Written by Grace E. Miller

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed August 3, 1917.

|

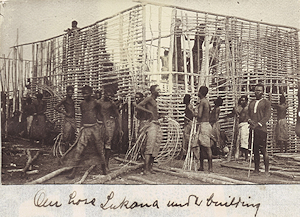

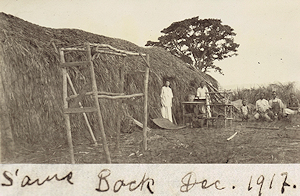

Mr. and Mrs. Sylvester Miller of near Rantoul, whose daughter, Miss Grace E. Miller, has been a medical missionary located at Luebo, Africa, the past two years, very kindly send The Republican a part of another letter received from their daughter. We have published several very interesting letters from her, which have been read with great interest by our readers. To this letter is appended the announcement of Miss Miller's marriage to a fellow worker in the mission field, which is proof that the little god Cupid has dominion in far away Africa as well as right here in Miami-co., Kansas. With this letter is enclosed a photograph of a native grass hut or house, with a young native in abreviated costume beside the hut.

The following is the letter:

|

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed August 3, 1917. - Click to see entire article.

|

Luebo, Africa, April 15, 1917.

My Dear Ones at Home.

The Lapsley will leave in the morning and I think the mail will go again this week. I try to send by each mail because I suppose the letters stand many chances of never reaching you now.

The river is higher now than it has been for two or three years. The mosquitoes are worse, also. I never saw so many of them. We are afraid of malaria, but so far I have kept well.

I have not heard from Bessie for months. (a friend, a missionary to India.) I have a cat here. He wants to help write, and because I won't let him, he is making all the diyoyo (noise) he can.

A new station is to be opened soon. I may be sent there, as the Doctor's wife is a nurse.

I received a letter from mother, which was written the middle of January, so you see it takes a long time for them to reach me. I'm afraid I do not receive all your letters. I am sending you some pictures.

Last Sunday one hundred and three natives were baptized. They are very strict in their examinations. The Kellersberger's goods have not arrived yet. I suppose they will be here the first of September.

Glad to receive Capper's Weekly, so glad to get the other papers, also the Christian Herald. Mother, will you please keep on sending my birth certificate until you get a letter from me saying I have received one. You will do me a great favor and I will be so thankful to you. Never forget to pray for us, I feel you remember.

Yours lovingly,

Grace E. Miller.

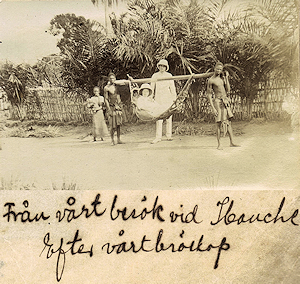

Later: Mr. and Mrs. Miller wish to announce the marriage of their daughter, Miss Grace E. Miller, to Mr. S. Edhegard, May 1, 1917. Mr. Edhegard comes from Sweden, is of Swedish parentage, is highly educated, has been connected with the Luebo work for some time and is a Christian minister. Hundreds of natives witnessed the ceremony, which we will try to describe later.

Yours truly,

S. and L. Miller.

From Far Away Africa:

Written by Grace E. Miller Edhegard

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed August 31, 1917.

|

Mrs. Edhegard, who is a daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Sylvester Miller, who live in Franklin-co., just across the line from Stanton, went to Africa several years ago as a medical missionary. We have published several very interesting letters written by her to her parents and we will certainly be glad to have her story of an African romance. Her letter referred to above was mailed June 3 and is as follows:

The following is the letter:

|

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed August 31, 1917. - Click to see entire article.

|

Luebo, Africa, June 3, 1917.

Editor of The Miami Republican:

Dear Sir: I understand you would like letters or other material from Africa, so I take the liberty to send this article to you. If you would send me the paper I would be glad to send you other articles or letters from time to time. You have known me before as Grace Miller, so perhaps you might some time like to hear the story of an African romance which made me

Grace Edhegard.

Luebo, Congo Belge,

Kasai Dist., Africa,

Care of A.P.C.M.

OUR LITTLE FRIENDS.

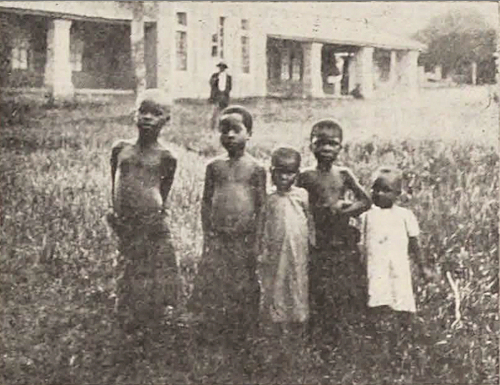

And who will care for the little orphans. What is to become of them? Can we simply ignore them and turn them aside to die? This is a problem which is being brought more and more forcibly to our attention. When these unfortunate little ones are brought to us in the hospital, having been neglected until disease has attacked their little bodies, then when they have become strong once more must we turn them out to perish or return again to us sick and miserable? We cannot make an orphans' home of the hospital, as we need all our room for the sick people. I would like to call your attention to a few of our little waifs who are still with us.

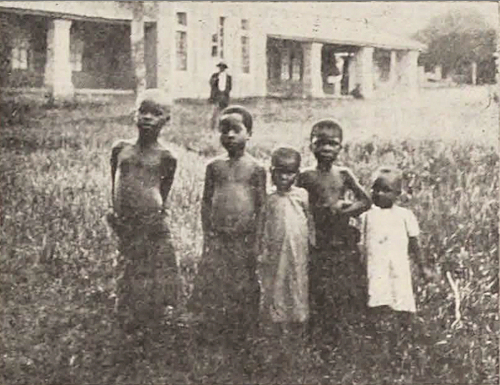

Little Abraham is now a little past two years of age. When he was a tiny, tiny baby he was brought almost dead to Miss Fair, who was then the only nurse at the station. He was a pitiful sight and everyone who saw him thought he could not possibly recover. But these little one show wonderful vitality sometimes, and with careful nursing he was well once more. As he had no friends he had been cast aside to die. His mother was dead, and as no one else wanted him he became hospital property. He sleeps in a big box and is very happy because he has such a nice house. He is very seldom sick, rises early in the morning and plays about until time for morning prayers. When he hears the call for worship he comes silently into our house, sits quietly through the service and tries to join in repeating the Lord's prayer. He knows some of it, but misses most of it and comes in very strongly with the amen. On Sunday he never forgets his shells to put into the collection box. The natives use shells for money, and Abraham would think it very bad to go to church without his shells.

Kayoka, standing next to Abraham in the picture, is probably five years old. He was living with a brother in the village but was practically without care. He wandered into the hospital yard one day and was a sight to behold. His poor little hands and feet were filled with jiggers and he was in great distress. You who do not know about jiggers cannot imagine his pitiful condition. Jiggers are small black insects, about twice as large as our chiggers, which bury themselves in the flesh, form a bag and fill it with eggs. When fully developed this bag is as large or larger than a good sized pea. When these are removed they leave a hole in the flesh, which of course is quite sore and if not cared for will become infected and probably in this climate cause a bad sore. If the jiggers are not removed they finally burst the bag, not only causing a worse sore, but scattering hundreds of eggs, which are ready to hatch and enter other toes and fingers. Poor little Kayoka had hundreds of jiggers, but he was very patient, crying pitifully to himself as they were removed and the many sores were dressed and bandaged. It was several days before they were all finished and then he was happy. Had he stayed a few days more in the village he would no doubt have lost several of his toes and fingers. Little Katoke who came to us just recently, has only one nail left on one foot, having lost the others from jiggers, and his foot is sore and badly swollen and infected yet.

Cibuabua is the only little girl we have kept for a long time after she was well. She is possibly four years old, a very bright little lass. A more loving little girl could not be found anywhere and she seems to be simply starving for affection. One of the missionaries found her one Sunday, or rather she found him and clung to him so he could not leave her. On inquiring he found her parents were dead and anyone who might have cared for her had deserted her, and she was left to shift for herself. Covered with sores and very thin and dirty, she was an object to arouse pity in anyone. Having been compelled to steal for a living, it was hard for her to realize that it was no longer necessary and that she would have plenty to eat without stealing it. She soon felt at home among the children, but was never satisfied unless some special attention was showed her. After she had been with us for several weeks and was quite well and strong again, we sent her to the girls' home, where she will have good care and training.

Mpanda Nxila is a little half-cast boy who lived with his grandmother. He was so thin he could scarcely walk, for she was too old to be able to find them both enough food. He had sores on his feet and legs, so we persuaded

her to leave him with us. Now he is well and happy, but if he should go away with his grandmother he would soon be in his former condition. He and Kayoka are about the same size and are always together, but I have never seen them fight or quarrel.

Musonguela is the oldest boy we have. His father drinks and the child does not want to live with him. The parents are separated and live in different villages, but if Musonguela should go to live with his mother then his father would steal him. He does not object if he lives at the hospital, so this is home to him. He works to pay his board and we have always found him trustworthy. He is probably ten years old.

And do the other children do nothing but play? Oh no, they have their little tasks which they must do every day. They carry the corn which the people bring in the morning to the dispensary to pay for their medicine. In the afternoon they sweep and run errands. They are always glad to help and it is surprising to see their interest in things. Mpanda Nxila, who is about six years old, decided one morning he would like to help operate, and standing on a chair to be able to see, he watched a long, tedious operation and was as quite as a mouse. Of course they are sometimes naughty and must be punished. They are full of mischief like all children and play all kinds of tricks on each other, but they are also happy and contented.

What will be the future of such unfortunate children as these? We do not know, but we hope the ones we have the privilege of helping will grow up to be men and women who serve and fear the Lord. At least we try to bring them up so that those who have known the deepest misery of heathendom may one day go forth and tell their own people about Him who bore all our sins and miseries in His own body. And we pray that He himself may add His blessing to our feeble endeavors.

Grace Edhegard.

This article was also printed in the January 1918 issue of The Missionary Survey. The photo of the orphans above was taken from that issue.

A Movie Show in Congo Land

(Version 1)

Written by Sixten Edhegard

Newspaper article from Capper's Weekly

of Topeka, Kansas printed October 20, 1917.

|

We would like to express our appreciation of Capper's Weekly, which we receive in Central Africa, in the Congo, the heart of Darkest Africa. We receive four or five when the mail finally comes. It comes to us addressed to Miss Grace Miller, but since romances may occur even in such an uncivilized country as Africa, I now have the pleasure of sending to your paper an article written by my husband.

GRACE E. EDHEGARD (MILLER).

|

Newspaper article from Capper's Weekly of Topeka, Kansas printed October 20, 1917. - Click to see entire article.

|

To the Editor of Capper's Weekly.

Everything the white man has, his manner of living, his behavior and actions are subjects for the Congo negros' wonder and amazement. In the eyes of the black man he is almost omnipotent, all-knowing and, with unlimited riches.

One of our missionaries had given several shows with a little moving picture machine he had received as a gift. Then a much better and larger one arrived from America.

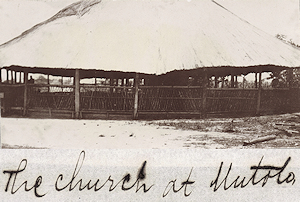

It was 7 o'clock in the evening and the darkness had already a long while rested over the mission station. A blanket and a sheet was put up between two poles in the shed we call the church. The chicken boy was ringing the big bell with all his might to bring the people together. I, myself, with a lantern in my hand and my pockets full of postcards and photographs stumbled along in the darkness seeking the narrow path, the other missionary after with the machine. The shed was

already filled to suffocation with a noisy and interested audience who were explaining to each other what was going to happen.

The first picture to appear on the sheet is a likeness of the oldest missionary and the rest follow in succession. They are soon recognized and applauded, altho in their white stiff collars and peculiar clothes they appear not a little queer. We have already warned our audience if they do not keep quiet and "peace" is not satisfactorily observed we shall finish and go home. Then satan himself appears on the cloth. That he would some time come back was very natural. They who were sitting closest had a hard time to decide whether he were harmless or not. Others were making grave threats. All were crying and stamping with their feet and clapping the hands and shouting as only children of nature can do.

After several unsuccessful attempts to give them an explanation, "peace" was restored only when another picture was unfolded before their wondering eyes. In beautiful succession came steamboats, landscapes, high houses, railway trains, etc., things they could not imagine were in existence, and in spite of all our assurances that everything was a reality we could not convince them. They were more than surprised to see white snow, which we told them was a kind of rain falling in the cold season in "Komputu," which is their name for every foreign land, and astonished to see water which by the cold was made so hard that one could walk on it. How could it be possible for those people to tie iron pieces on their feet and run on water as the picture showed? Angels with white wings and glittering dresses were also very interesting pictures.

When at the close an old chief, who according to his own statement and that of others, is supposed to be 3,000 years old, came to view a photograph of him I had taken, neither their good sense, behavior or quietness could endure it longer, the noise exceeded all possible description and we had to finish the entertainment, which had lasted a little more than one hour.

The next day came a crowd of those who had seen the pictures the night before and asked if the devil was really so terrible as they had seen him on the sheet. When I told them he was not only so bad, but much worse, they all pledged that from that day henceforth they would never have anything to do with him.

SIXTEN EDHEGARD.

Mission Luebo District, Belgian Congo, Africa.

Foreign Missions

Written by Wade C. Smith

WADE C. SMITH, Editor

Magazine article from The Missionary Survey printed November 1917.

Published monthly by the Presbyterian Committee of Publication, Richmond, Virginia

|

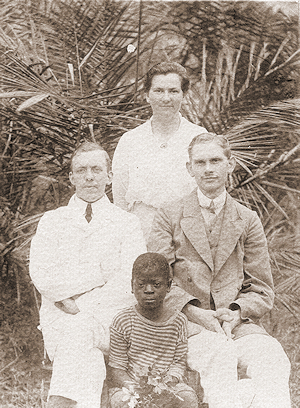

THE submarines have evidently intercepted some of our African mail. One letter that found its way through brings the information that Miss Grace Miller, who went out a little more than a year ago as a trained nurse to Africa, was married to Rev. Sexton N. Edhegard. Some other letter which must have been written giving the date and circumstances of the event has not yet found its way through.

|

Magazine article from The Missionary Survey printed November 1917. - Click to see entire article.

|

Mr. Edhegard is one of several Scandinavian missionaries who have gone out to the Congo and are being supported by their home societies, but who have been working in connection with our mission while waiting for things to quiet down so that they can regularly organize the work which they expect to undertake under the direction of their own society. Their presence on the field was a great help to our mission during the time that so many of our own missionaries were being detained at home on account of the prevailing conditions of travel, and we hope that this copy of THE SURVEY will in due time come into their hands and convey to them the assurance of our gratitude and appreciation of the services they have rendered.

Foreign Missions

Written by Wade C. Smith

WADE C. SMITH, Editor

Magazine article from The Missionary Survey printed June 1918.

Published monthly by the Presbyterian Committee of Publication, Richmond, Virginia

|

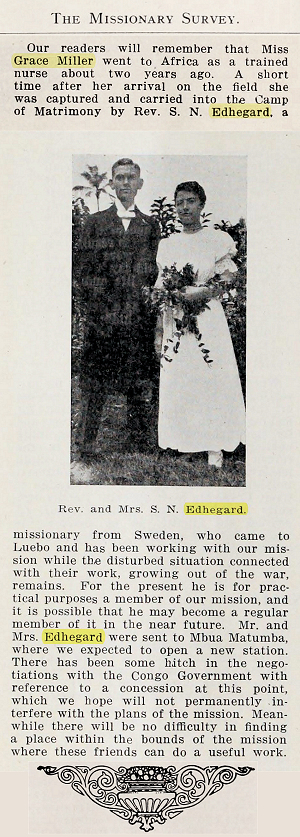

Our readers will remember that Miss Grace Miller went to Africa as a trained nurse about two years ago. A short time after her arrival on the field she was captured and carried into the Camp of Matrimony by Rev. S. N. Edhegard, a missionary from Sweden, who came to Luebo and has been working with our mission while the disturbed situation connected with their work, growing out of the war, remains. For the present he is for practical purposes a member of our mission, and it is possible that he may become a regular member of it in the near future.

Mr. and Mrs. Edhegard were sent to Mbua Matumba, where we expected to open a new station. There has been some hitch in the negotiations with the Congo Government with reference to a concession at this point, which we hope will not permanently interfere with the plans of the mission. Meanwhile there will be no difficulty in finding a place within the bounds of the mission where these friends can do a useful work.

|

Magazine article from The Missionary Survey printed June 1918. - Click to see entire article.

|

A Movie Show in Congo Land

(Version 2)

Written by Sixten Edhegard

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed March 22, 1918.

|

Mr. and Mrs. Sylvester Miller of near Rantoul have just received a letter from their son-in-law, Mr. Edhegard, who is a missionary stationed at Luebo, Congo Belge, Africa, which tells interestingly of the effects of motion pictures on the natives there, which they kindly send us for publication. Mrs. Miller writes that her daughter Grace, who went as a medical missionary to Africa several years ago, where she met and married Mr. Edhegard, will soon write them a letter, which we may also have for publication. We have published several of her letters, which have been very interesting and were read with much interest by our subscribers. The following is Mr. Edhegard's letter:

|

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed March 22, 1918. - Click to see entire article.

|

To the Editor of Capper's Weekly.

Everything the white man has, his manner of living, his behavior and actions are subjects for the Congo negroe's wonder and amazement. In the eyes of the black man he is almost omnipotent, all knowing and, with unlimited riches.

One of our missionaries had given several shows with a little moving picture machine he had received as a gift, then a much better and larger one arrived from America.

It was 7 o'clock in the evening and the darkness had a long time rested over the mission station. A blanket and a sheet were put up between two poles in the shed we call the church. The chicken boy was ringing the big bell with all his might to bring the people together. I with a lantern in my hand and my pockets full of post cards and photographs stumbled along in the darkness seeking the narrow path, the other missionary after with the machine. The shed was

already filled to its limit with a noisy and anxious audience who were trying to explain to each other what was going to happen.

The first picture to appear on the sheet is a likeness of the oldest missionary, and the rest follow in succession. They are soon recognized and applauded, although in their white stiff collars and peculiar clothes they appear not a little queer. We have already warned our audience if they do not keep quiet and peace is not satisfactorily observed we shall finish and go home. Then satan himself appears on the canvas. That he would some time come back was very natural. They who were sitting near had a hard time to decide whether he was harmful or not. Others were making grave threats, all were crying and stamping and clapping the hands, and shouting as only children of nature can.

After several unsuccessful attempts to explain to them, peace was restored only when another picture was unfolded before their wondering eyes. In succession came steamboats, landscapes, high houses, railway trains, etc., things they could not imagine were in existence, and in spite of all our assurance that everything was a reality, we could not convince them. They were amazed to see white snow, which we told them was frozen rain falling in "komputu," which is their name for "other lands," and astonished to see ice and that people could walk on it - it surely could not be true. How could it be possible for these people to tie iron pieces on their feet and run on water? Angels with white wings and glittering garments were very wonderful.

When at the close an old chief, who according to his statement and others, is supposed to be 3,000 years old, came to view, (a photograph of him I had taken), neither their good sense nor behavior could endure it longer. The noise exceeded all possible description and we closed the entertainment, which had lasted over an one hour.

The next day came a crowd of those who had seen the pictures and asked if the devil was really so terrible as they had seen him on the canvas. When I told them he was not only so bad, but much worse, they all pledged that from that day henceforth they would never have anything to do with him.

A Missionary Cat.

Written by Grace E. Miller Edhegard

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed March 29, 1918.

|

Mrs. Grace Miller Edhegard, who sends us the foregoing very interesting letter, is the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Sylvester Miller, who live near Rantoul. She went to Africa several years ago as a medical missionary, where she met and married Mr. Edhegard, who is also a missionary there. The Republican and readers will be more than pleased if Mrs. Edhegard will send us accounts of the two weeks' trip in the Congo, also of her meeting with her husband and her marriage. We will look for these lat- er. As will be seen by the date, her letter was written December 4, and was received here last Sunday, March 24, requiring three months and twenty days to make the long trip from Africa to Paola.

|

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed March 29, 1918. - Click to see entire article.

|

Mbua Matumba, Africa, Dec. 4, 1917.

care A. P. C. Luebo, Congo, Belge.

Editor of The Miami Republican:

Dear Sir: I am enclosing you herewith a small article which I thought

would be interesting at least to children. If you care to print it you are

free to do so. I am finishing a long article about our two weeks' trip in the

Congo, which I would be glad to send

you for publication if I knew you cared

for it. The trip was quite interesting, although tiresome, and I thought

would be even more interesting to

those who like to read about a land

where the people are so little civilized as we find them here. If you would

like to have it, just let me know, and

I will send it later. Remember, however, that it takes probably three

months for your leter to reach me and

that length of time for an answer.

Hoping that all your Miami Republican readers are in the best of health

and still enjoying the paper, I am,

Most respectfully yours,

Grace Miller Edhegard.

P. S. I think it would make an interesting story if I should describe my

meeting with my husband and our

marriage in Africa and the life of

traveling since. Do you think so?

A Missionary Cat.

Written by Grace E. Miller Edhegard

Perhaps you think it strange that a

cat could be a missionary just like

real people, but I think you will agree

with me before you have finished reading this little story. You may think

it would have been better to have called him the cat of a missionary, but I

cannot agree with you, because are not

people who help missionaries often

called missionaries, too? Besides, Pele

not only helps missionaries but he is

somewhat of one himself. He once

was only a common heathen kitten,

and although he has still some heathen ideas and ways, yet we think that

he has greatly improved.

Rats are very common and plentiful and become very troublesome in

Congo land. They seem to think that

the house belongs to them, especially

after dark, and no matter how much

you need a good night's sleep and want

a quiet hour, they proceed to romp

everywhere and have a regular jubilee

right in the middle of the night.

Well, things were becoming quite

serious in one missionary's home, for

not only did these pests keep a continuous uproar at night, but they also

insist on eating clothes and letters

and other things. Poison failed to

kill them, so as a last resort it was decided that a cat was a necessity. Pele

was brought from the native village,

a poor little heathen kitten. He was

very homesick at first and refused to

eat, and it was necessary to coax him

by giving him tempting morsels from

the hand. Although he seemed a harm-

less cat, yet the cowardly rats respected his power so much that peace

reigned once more and it was possible

for the kitten's new master to get a

good rest and leave his papers on his

table at night without their being eaten while he slept.

Pele became much attached to his

master and when he left on a trip to

visit some distant village he hunted

everywhere for him and sometimes it

seemed that he would pull all the

curtains from the windows and clothes

from the tables unless he found that

for which he was seeking. He was

very happy on his return, and his delight was quite evident in his change

of action.

The usefulness of Pele was without question, and when it became

necessary to remove permanently to

a distant village, a journey of nearly

two weeks by hammock, of course

Pete, who had now become a large cat,

must be taken along. Poor puss must

have realized that traveling in Congo

for several days would not be very

pleasant, and in spite of his love for

his master and mistress he ran away

and could not be found when the time

came to start. Regretfully they went

without him, thinking of the times

past when they longed for peace and

quiet at night and of the times afterward when, because of puss, they had

been able to live free from the tormenting rats. Fortunately shortly after their departure Pele thought it

safe to venture into the open again, but

he was at once put into a kind of native basket and sent after the party.

At midnight that night he awakened

his owners by his wild and frightened crying. He was very much distressed and did not become reconciled

until taken from his jail and tied inside the house near their beds. Every

day when the caravan was ready to

start he began to cry and did not stop

until night when they stopped to

camp. In fact, just as soon as his

basket was in sight in the mornings

his wailings started. Poor puss, he

thought it a very poor life during the

day, but was quite well satisfied at

night. When the first week was ended and the caravan stopped for a few

days at a mid-station, before going the

cat seemed to feel at home wherever

his friends were. He did not like to

be left alone at night and insisted on

taking walks with them, but during

the day was very well satisfied if he

only had something to eat. At last,

the time of starting on the remainder

of the journey came. Puss seemed

to realize that something was to happen, for he was uneasy all the morning, and although they tried to reconcile him he again commenced his crying. This time, however, he had a

more comfortable basket, and when

it was covered with a dark cloth and

tied securely to the pole of the hammock, it was a very good sleeping

place for him, and after some time

he made this discovery and had many

good naps instead of continually struggling to escape. He did not altogether give up the attempt, however, and

one day escaped on a big plain. This

plain was the very worst place he

could have chosen for a home, for it

was only a desert waste and starvation was certain. How the hammock

men did chase poor puss and he thot,

I suppose, they would kill him and did

his very best to get away, but it was

useless, and they came triumphantly

back and Pele was so out of breath

they though for awhile he would die,

but he was only worn out and needed

a fresh breath.

The natives are not accustomed to

treating animals with kindness, so it

was a queer sight, they thought, when

food and water were provided and

kitty's comfort considered. As new

villages were passed, many of them

where a white woman had never been

before, the natives were much excited

and made plenty of noise. This frightened the cat and he would cry pitifully. As they could not see into the

basket but only hear the cries, the

natives said there was a baby in the

basket and thought they had been

treated badly because "mama" did not

show them the baby. The men in the

caravan told them over and over it

was an animal and that the white

"mamas" did not carry their babies

shut up in a basket.

The tiresome journey was at last

at an end. Pele was probably one of

the happiest of the party and he proceeded to make himself at home. He

is perfectly satisfied now except when

left alone, and that he does not like

at all. He refuses to stay alone in

the evening, but takes his walk when

his friends go out. He is being a missionary every day by showing the natives they should treat animals with

kindness.

In this article Grace promised to write about how she met and became engaged to Sixten. Many of her letters from the Congo never arrived in America. We can only assume this was one.

A Journey Through the Congo.

Traveling in Africa - Preparing for the Journey - Day 1

Written by Grace E. Miller Edhegard

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed May 10, 1918.

|

With pleasure we have the privilege

of presenting herewith another very

interesting letter from Mrs. Grace

Edhegard, daughter of Mr. and Mrs.

Sylvester Miller, of near Rantoul, who

is a medical missionary located at

Luebo, Congo Belge, Africa. She writes:

|

Newspaper article from The Miami Republican

of Paola, Kansas printed May 10, 1918. - Click to see entire article.

|

Dear Friends: I thought perhaps an

account of our trip of ten days in the

Congo would be interesting to you so

I take the liberty to send it to you.

As it is rather long and the mails so

uncertain these times I am sending the

account of each day separately.

A Journey Through the Congo.

Written by Grace E. Miller Edhegard

Perhaps you would be interested to

hear about the preparations necessary

to be made when moving in the Congo,

especially when there is a long journey

ahead. One who has never travelled

in this country cannot imagine how

much hard work must be done before

a person is ready to leave civilization

and go into the heart of a heathen

country and start a new home. Although missionaries do not have a

great many things, yet when the mere

necessities are packed in boxes not

weighing more than one hundred or

one hundred and twenty pounds, you

almost consider yourself far from being a pauper. The boxes must be

large and heavy, because they are

carried by native men who are human.

They tie the box to the middle of a

pole, and with the ends of the pole on

their shoulders, the two start upon

their journey. The path is often very

narrow and sometimes the way goes

straight up and down the hill. It is

really necessary to pull ones self up

by roots and shrubs growing by the

path, and when the top is reached it

seems that if another hill is in sight

it will really be more that you can endure. How the men climb these places

with their loads I have never been

able to understand.

Well, we started to pack nearly two

weeks before we intended to start and

sent one caravan on ahead. When the

day of departure arrived we still had

a little left and we worked as hard as

we could, but when the noon hour came

around we still found some things yet

unpacked. How you puzzle over the

best place to put each thing. What a

problem to know just what you might

need in the path and before you will

be able to open your boxes and trunks

again. At last the chop boxes for the

road and other articles which we expect to use on the way are ready and

we decide that it is the best thing to

have a little something to eat before

going. Fortunately for us, our friends

were kind enough to invite us to eat

with them before leaving and we surely

did justice to the dinner. After the

meal we must say good-bye to all who

are to be left behind, and as there are

eight families it is well toward the

middle of the afternoon before this

painful task is completed. Some way

it is always a great relief when this

part is over and you can be left alone

to think it over and reconcile yourself to your new circumstances.

It is nearly four o'clock, but since

we do not have a long journey before

reaching the place to spend the night

which our schedule gives it is just as

well it is not earlier, because the sun

is very hot up until three-thirty or

four o'clock. Can you imagine us as we

start? We do not have a horse and

buggy, nor a car, not ever street cars

or railroad trains, and it would be impossible for a white woman to make

such a journey as lies before us

on foot. It would really be quite difficult even for her husband, for I am

sure that he would be ready to have a

long spell of fever by the time the

destination was reached. The natives

carry us. No, not on their backs, but

in hammocks suspended on long poles.

These poles rest on their shoulders in

the same manner as the poles of the

box carriers. Many of the missionaries

have hammocks made of canvas, but

these we had were made of a pliable

kind of vine which is very strong and

can be woven into any shape desired.

These hammocks were very comfortable when you have two or three

cushions to relieve the tension of the

muscles. We have six men apiece and

they carry from two and a half to three

hours by turns. Sometimes the way is

tiresome to them, but as we walk up

and down the hills a good hammock

man looks forward to the road life

with joy rather than with dread. They

are anxious to be off now, for some

of these men come from this far

section of the country and have not

been back to their old home for years

and they are hoping after the two

weeks of traveling to greet at least

some of those whom they have not

seen for so long.

With a farewell look to the station

we go down our first hill and our dear

old home is lost to our sight. Will we

ever see it again? We cross the river

in a boat and go up a hill and now

we feel we have really started on our

long and tiresome journey. Were we

traveling in a civilized country and

with the conveniences which this civilization affords we would not think

much about it, for it would mean only

a couple of days, perhaps not so long

as that. How glad we are now that

we do not have far to travel before

the first stop, for we are both so tired

after the day of work. It is dark soon,

but with a nice moonlight it is so

pleasant to travel. We safely reach

the house of the chief with whom we

are to spend the night. By this we mean

he is so friendly that he divides one of

his houses with us or rather shares it

with us. The house is quite large,

having three rooms, and he removes

everything from the center one and

gives us the right of way. Fortunately

one camp bed and chair arrive at

about the time we do, so we can get

a little rest. We look and look in vain

for the rest of our camping things, but

through some misunderstanding they do not arrive, so we content ourselves

the best we can.

Back of the house in which we stay

the chief has a semi-circle of houses

which are occupied by wives. This

chief is not a young man. In fact, one

of his boys is probably twenty years

old. This old chief was at the hospital

for some time, also this young man and

his mother, so it seemed like meeting

old friends to see them again. The

tribe is not very large, but they are

among the most civilized of any of the

heathen tribes I have met. Not in the

matter of religion, but in regard to

their ambition to work and their interest in foreign things. They are very

friendly, and to show this the chief

brings us a goat. It is almost

impossible to accept this gift, but if

one refuses the gift of a native they

are grievously offending him. Then,

too, when a native gives a gift he always expects one in return, which

amounts in value to more than the one

he has given. We explain as best as

we can that we have just started on a

long luendu or journey but if he would

like to give us something we could

take, a chicken or some small gift, as

our men were already well loaded. He

seemed to understand the situation and

in a short time brings a chicken and

about two quarts of rice. In a few

minutes one of the wives feels it her

duty and privilege to give something,

so she comes with a chicken and some

more rice. Of course we accept quite

graciously, because it would be very

poor policy to refuse and lose all posibility of being able to do work there

through the mission teacher. The rice

we cook for the hammock men, who

are always glad to receive something

to eat, because then they do not have

to spend the money which has been

given them to buy food on the road. I

should say "salt," for the money of the

native, in most cases, is salt, heads or

shells.

In vain have we waited for our camp

goods to arrive, so we boil a few eggs

which were given us just before leaving

and after eating these we feel a little

stronger. As we are both so weary

we find we can both rest fairly on one

camp bed. I must admit, however, it

was a little bit crowded, but that is

only a start in road life. The natives

always build a fire in their rooms and