Chapter 18

MOVING ABOUT

We took the bus to New Orleans where Mim and Grandma were waiting to receive us. I have nothing but affectionate memories of these two fine ladies. They were always ready to help. No one ever did more for Shirley and me.

When Felipe, Jr., celebrated his first birthday that December, Mim and Grandma baked a big birthday cake and we had a party. The baby had a grand time. Shirley's illness was diagnosed as pregnancy. Things didn't look so good for employment. Here we were, expecting our second child, and I was jobless.

The International Seamen's Union the union I had been a member of was on strike on the East and Gulf Coasts. One of the strikers' demands was the ouster of the incumbent union officials the same union officials that had refused to help us Filipinos. I didn't wait for an invitation to join this unofficial rank and file strike. I was glad to register for picket duty the day after I arrived in New Orleans. And, I was glad to donate a few dollars to the "stewpot" an act which gave me instant recognition with the strike leaders. I took advantage of the strike and urged a number of Filipinos, former shipmates, to do the same. This was our chance to show what kind of working men we were. We had nothing to lose, anyway. Most of us were unemployed.

My donation to the "stewpot" made me a popular striker and I took advantage of the situation. I became active on the picket lines and in the union meetings and was assigned to the food committee. It was an important assignment, for we had to beg for every loaf of bread and every pound of meat we fed the strikers. Since the strike was unofficial, we had very meager funds.

That 1936 37 seamen's strike gave new dimensions to American seamen, including the Filipinos who had remained faithful to the cause. Although we were out of work, none of the Filipinos "scabbed" and our relations with the mainstream rank and file seamen became solid. Though we did not succeed immediately in getting rid of our corrupt union officials, our efforts and sacrifices during the struggle paid off. There were elections among the workers of many individual steamship companies. Finally, the strikers, led by Joseph Curran, ousted the old officials. A new maritime union was formed following the disintegration of the old International Seamen's Union.

Shirley was getting nearer to the end of her pregnancy and her mother asked us to come back to Mobile. When we returned, we discovered that Big Daddy had sold our house while we were in new Orleans. He had never given us the deed. We made arrangements with Shirley's Uncle Jesse, who lived at Eight Mile, for Shirley and the baby to stay with them for thirty dollars a month. I would live near the waterfront in Mobile with a group of Filipinos who, like me, were looking for shipboard jobs. When I could, I would stay with Shirley at Uncle Jesse's on weekends. I would pay extra for my groceries.

Our money was running low, we were expecting a baby, and we had no home or furniture. But, I had hope. Filipinos were beginning to get shipboard jobs again, mostly on oil tankers. I would take any job: messman, anything.

April came and disaster struck again. I went to Eight Mile one weekend, and Uncle Jesse told us to find another place to live. Where could we go? My mother in law was the only person who would help us and she was in the hospital. Besides, she didn't have a home of her own. She was living with her rich brother, Shirley.

I called my "New Orleans family" and Mim urged us to come "home". I was crying when I left the phone booth. Before I could compose myself, an angel, in the person of one of my old messboys, appeared. Frank Pundawella. He, like myself, was married to an American girl and they had one son. The similarity ended there. Though, like me, he was an unemployed seaman, he had a wife with a father and mother who could help them. True, they were living hand to mouth in a low rent house. They were a "family", though, and we could live with them.

I told Frank our predicament and my plan to go to New Orleans to live with my cousins. He reminded me that he had started shipping men from our newly formed union and that I was nearing the top of the shipping list. He told me his family had a spare bedroom. It was bare not even one piece of furniture but we could live in it.

I accepted his offer at once and went to a second hand furniture store in Prichard, where I bought a used mattress for two and a half dollars, delivered. So, with a mattress on the floor and some old pillows and sheets Frank gave us, we moved in with Frank's in laws, the Tucker's.

We were a godsend to them. None of them had a regular job. Mr. Tucker eked out a living by making and selling "floor sweep" to barber shops and stores with wooden floors. "Floor sweep" was a mixture of sawdust and discarded automobile oil, both free for the asking from saw mills and service stations. They were practically destitute. They owed back rent. There was not enough money for

groceries. The second day after we moved in, the electric company came to discontinue service for nonpayment of bills. Our little savings rescued them.

Shortly after we moved in with the Tuckers, I got a cook's job on a small coastwise tanker. We made only the Gulf ports: New Orleans, Houston, Beaumont, and Mobile. We stayed only a few hours in each port.

The two months I spent on this small tanker were the most rewarding and the luckiest for me. The pay was good on tankers and the crews did not have much port time to spend their money. Poker games were popular on most ships, especially on the oil tankers. I am ashamed to admit I disregarded Mr. Hall's advice on gambling. The short time I was on this small tanker, luck and my oriental patience my willingness to wait for a better chance paid off handsomely. I won several hundred dollars. Shirley and I were able to buy some furniture and move into one of Big Daddy's houses in Prichard. There was even money to put in the bank. Our second son arrived on May 30, 1937, and we named him Vincent, after my father.

The few hours that the small tanker spent in port in Mobile were not enough for me. I wanted to spend more time with my family. Besides the short port time, we docked at the other side of Mobile River and had to cross on a rowboat to the Mobile side. With several hundred dollars in savings and the security of the new union's rotary shipping system, I quit the oil tanker. I had a sure job. All I had to do was wait for my number on the job list to come up.

Shirley's mother moved in with us and we began to live a normal family life again. I got a job on another tanker, the S.S. Dora. She was on the molasses trade to Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Atlantic and Gulf ports. I was the chief cook. After two trips, the Chief Steward quit and I was promoted to his job. Things were looking brighter for Shirley and me. She began meeting me in other ports, such as New York, Baltimore, and Philadelphia.

|

The recession of 1938 came and ships were tied up for lack of cargo. In July, we were ordered to tie up in New Orleans after discharging our cargo of molasses. I was not worried. I had saved several hundred dollars and I knew our union rotary shipping could be depended on for another job. But coming up the Mississippi River, I became concerned when I counted over twenty ships, idled for lack of cargo. I knew they were "dead" idled ships because no smoke was coming from their stacks.

|

|

|

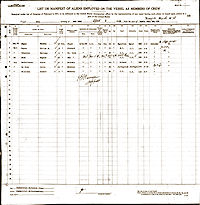

S.S. Dora manifest showing Felipe on line 2.

|

I decided to stay in New Orleans with Mim, who had remarried, and her two daughters. If my ship took on another crew, I would be entitled to my former job as chief steward. Mim had moved out of Grandma's and was living in the northeast area of New Orleans, five or six miles from the old Royal Street house.

I was registered at the bottom of a long list of unemployed seamen. I feared it would take me months to land another job, as only unsubsidized cargo ships and oil tankers were open to non citizens. To compound the hardship of non citizen Filipinos, we, along with other Orientals, were not eligible for American citizenship if we had not served in any of the armed services. This law was not changed until after World War II.

Continue to next chapter...

(Introduction)

(Contents)

(Chap 1)

(Chap 2)

(Chap 3)

(Chap 4)

(Chap 5)

(Chap 6)

(Chap 7)

(Chap 8)

(Chap 9)

(Chap 10)

(Chap 11)

(Chap 12)

(Chap 13)

(Chap 14)

(Chap 15)

(Chap 16)

(Chap 17)

(Chap 18)

(Chap 19)

(Chap 20)

(Chap 21)

(Chap 22)

(Chap 23)

(Chap 24)

(Chap 25)

(Chap 26)

(Chap 27)

(Chap 28)

|