Chapter 25

AFTER THE WAR

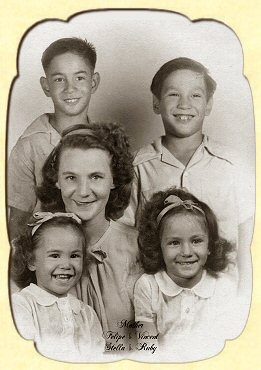

I found our children had grown a lot, especially our youngest, Stella. She did not know me at first. Pre teen age children grow considerably in 13 months and I was amazed at their growth. That long trip helped us to pay off our home and to buy the latest model car.

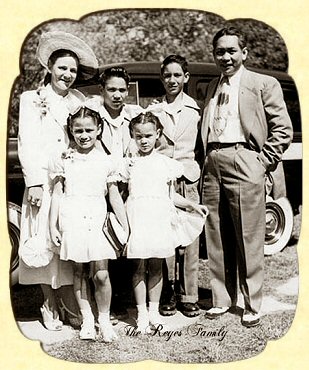

Reyes Family - Click each photo to enlarge.

Felipe, Vince,

Shirley,

Stella, and Ruby

|

Shirley, Vince, Felipe, Felipe Sr.,

Ruby, and Stella

|

My experience in the old ISU and later the NMU taught me that passivity and docility in an economic struggle was no asset to one who was a non citizen and belonged to a minority group. I became very active, vociferous, and outwardly militant in the SIU. My voice was heard and my presence noted in most of the union meetings where I championed our union causes and policies.

This did not escape the attention of the union hierarchy. Many of them became my friends and even confidants. I served on the policy making committees in the 1946 General Strike, the last of its kind. I was often elected chairman or secretary of the union meetings. My stock and stature in the Seafarers International Union was growing and by the time I took a ship after the General Strike, I was well known in the union circle in Mobile.

The S. S. James Kyron Walker was supposed to make a three week run to Trinidad but after she discharged her cargo, we were ordered to pick up a full load of grain from Argentina for Norway. That trip lasted almost six months. I was then a full member of the SIU and could be assigned by any contracted company as chief steward on any of its ships, but I preferred to sail with Waterman.

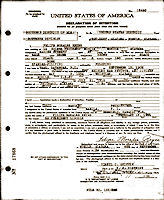

When I returned from Norway, I heard the best news of all: I would become a U. S. Citizen. I had been hoping and praying for this for many years. After the war, the government had changed the naturalization laws giving residents of Oriental origin who served during the war the right to become U. S. Citizens. I received my citizenship in a unique way. Because I was a merchant seaman and through the interception of my sponsors Captain Stewartt, a Waterman Vice President at the time, and Shirley Cochran, my wife's uncle I was sworn in alone. Present with me were my two sponsors; the Director of Naturalization and Immigration for the Port of Mobile; the clerk of the court; and Judge McDuffie, one of the authors of the Philippine Independence Bill. Finally, I became a U. S. citizen. How proud I was!

U.S. Naturalization Documents for Felipe.

Click each photo to enlarge.

Mobile, Sept. 6, 1934.

|

Mobile, Nov. 2, 1943.

|

Mobile, Nov. 2, 1943.

|

After I obtained my American citizenship, I was assigned as chief steward on the S S De Soto. She was on the European run and carried twelve passengers. She made the Gulf ports only and I was allowed by the captains to miss her from Gulfport to Mobile. So, I always had three or more days in Mobile.

S.S. De Soto manifest listing Felipe in 1948.

Click each photo to enlarge.

New York, Feb. 27, 1948.

|

New York, Apr. 14, 1948.

|

Mobile, May 8, 1948.

|

In late 1948, the De Soto still carrying twelve passengers was placed on the coastwise run. We made seven ports in 28 day trips and always paid off in Mobile. Every month, Shirley loaded the children in the car and drove to New Orleans to meet the ship. We stayed with Mim. When the ship sailed, I would ride back home in the car with my family and rejoin the ship in Mobile. That was ideal for me. My total service on the De Soto was almost seven years.

In 1949, the DeSoto went on drydock for inspection and minor engine repairs and stayed in Mobile over two weeks. During that time I was accepted in the Masonic order. It was one of the happiest times of my life. After the DeSoto's inspection, we discontinued passenger service.

In 1953, the union assigned me as an organizer of a big tanker company which employed Filipinos in most of its twenty ships' steward departments. During these seven months, I lived in Port Arthur, Texas, with several union officials who later became vice presidents of the union. It was during this time that I became close to the high echelons of our union hierarchy.

After my return to the De Soto in 1954, I learned that I had the best feeding record of the four coastwise ships. That is, my feeding cost was the lowest and crew complaints were the fewest. The seven years I was on the De Soto, I worked under six captains. In 1955, the McLean Interests bought the Waterman Steamship company and its other two lines, the Pan Atlantic Steamship Company and the Puerto Rican Line.

It was during this time that I saw Scotty Ross in the union hall. He was no longer top dog in the union. He was just a plain seaman, shipping as fireman. We talked about the old days, which he was reluctant to discuss. Several days after our conversation, I was told that he was in the hospital dying of a heart attack. I don't know what motivated me, but I went to take him some cigarettes. It was then that I mentioned the old union which he headed in Mobile. He told me how the young Turks of the Union which replaced the old ISU ousted him. He was close to tears when he realized that the one who asked for his help and did not receive it took the time to come and visit him and even brought him some cigarettes. He died in the hospital a week later and was buried in the Waterman lot in a Mobile cemetery indicating that he did not leave enough money to be buried. His wife had divorced him years earlier. Such is the wheel of fortune.

The committee drafted some rules and guidelines, most of which were my work. Three different steamship companies agreed to appoint one of their chief stewards to ride their ships as consultants and establish the new system: one for Seatrain with four ships, one for Alcoa with 11 ships, and one for McLean with 39 ships. By the end of 1955, I was the only consultant left. I rode all the company ships from one domestic port to another, staying on a ship from three to sixteen days to establish the system. I gave top priority to ships where the crew complained of the food or the company reported a high cost of feeding.

The Vice President of the company, Capt. Anthony, reported that the company realized a savings of over $200,000 in 1956. Union President, Paul Hall, learning of this result, bargained with all the steamship companies contracted to the union to adopt this system, with every company contributing so much per man per day to a fund to be administered jointly by the companies and the union. I attended many meetings in the union headquarters in New York with various company port stewards or marine superintendents to explain to them how the system operated.

By the end of 1959, most of the companies contracted by the Seafarers International Union were signatories to the contract. Thus was born the Plan of the Atlantic and Gulf Contract Companies which became the Food and Sanitation Department, then the Andrew Furuseth Training School, and finally the Harry Lundeberg Seamenship School at Piney Point, Maryland. From the five cents per man per day the companies contributed to the fund at the start, it grew to over two dollars per man per day.

And, what about me the one who contributed the most to its development? As a consultant, I was my own free agent. I was paid the regular union patrolman's wages, plus expenses whenever I was out of town. Waterman was paying into the pension plan for my pension. When the union took over the Food Plan in 1959, I became an employee of the entity instead of a free agent. I received the same wages and lost my contribution to the Pension Plan.

I was McLean's Food Consultant and the only one in the industry after the two consultants from the other two companies were discharged in 1955. I was the man who convinced the port stewards of other steamship companies to adopt the new system yet when it became a contractual provision, the union appointed two men one of whom was a brother in law of a union vice president to be over me. In 1960, when the union started a training program, funded by the Andrew Furuseth Training School, I was transferred to the Port of Houston and became the director of the school in the port.

Normally, I had ten to fifteen trainees. They received no training at all for shipboard work, but were assigned to entry ratings on the ship when no union members were available. I contracted with boarding house keepers to house and feed those trainees at three dollars a day.

In other ports, particularly New York and New Orleans, it cost twice as much to maintain the trainees. I was pressured to raise the three dollars by the Gulf District Director. I refused because the boarding house owners were satisfied with our agreement and were not asking for an increase in payment. Besides being the titular head of the union so called training school, I was doing union work like paying off ships and settling disputes between the crew and the captain; visiting the hospital weekly and paying hospitalized members their weekly hospital benefits; attending conferences and meetings to represent the union; and any other work given to my by the port business agent. When I reminded him that those were not my duties, he declared that I was working for the union and not for the Food Plan. I was paid by the Plan, though.

A man who was supposed to be my assistant would not take orders from me, claiming he was an employee of the union even though his checks were issued by the Food Plan. In 1967, my relation with the port union agent became so intolerable that I was thinking of resigning and going back to sea. This union agent had received many personal favors from Shirley and me. I had loaned him money and we had takem care of his two daughters while his alcoholic wife was being dried out in an alcoholic unit. There had been other personal favors, too.

In the summer of 1967, the union bought the former Navy submarine training base at Piney Point to be used as a training center. Certain training directors from other ports were sent to Piney Point to help with the renovations and enlargement of the existing facilities and other work there. I was among the chosen ones.

Shirley had just come out of the hospital when I was told by the Gulf Director in New Orleans of my impending move. No amount of argument could persuade him to let me stay in Houston. My telephone calls to the high union officials my friends were not returned. I knew then that my days as a member of the official staff of the Food Plan were numbered. But I would not give them any excuse to fire me, so I went to Piney Point.

Paul Hall, the President of the Seafarers International Union, was recognized as one of the most powerful labor union leaders in the United States. Besides heading the SIU and its affiliates, he also headed the Maritime Trades Department of the AFL CIO which numbered over six million members. Like many other union bosses, he did not reach his position by being meek, kind, and considerate. He was egotistical, supercilious, and demanding but he was also a brilliant negotiator and his knowledge of the maritime industry was unmatched.

It was rumored that he demanded the maximum to the point that it would not break a company from the industry for his people. From his subordinates, the lower echelon of the union hierarchy, he demanded complete and unwavering fidelity. He was ruthless when it came to handling those who wavered and did not carry out to the fullest the policies he proclaimed. He was the SIU itself, and the union boards and committees were nothing more than window dressings to comply with legal requirements or to appease membership demands, which occasionally occurred.

So, it was in the summer of 1967 that Paul Hall summoned many of the Food Plan officials (who, legally, were not employees of the union) to Piney Point. Shirley had just come out of the hospital following major surgery and I was not happy at all at being ordered to Piney Point. I was told in no uncertain terms that if I wanted to continue in my current position, I would have to go to Piney Point.

After two days of doing very little in Piney Point, I asked Paul Hall if he could dispense with me and let me go home, giving him my reason. Again, he told me if I wanted to stay on the payroll, I'd have to work at Piney Point. In the meantime, my assistant was put in charge of the trainees in Houston. I told Paul Hall that at the end of the week I would go home to make arrangements for Shirley's moving with one of my children and that I would return to Piney Point.

Evidently, he did not agree with my request. He showed his disfavor in a subsequent meeting he called for his staff members. There the things I heard about him how he treated other union officials were confirmed. While he was showing his authority by berating his subordinates in a meeting, he reminded me that there was a plane leaving soon. I took the hint. I agreed with him and left the meeting. I returned to Houston to quit my job. I registered to ship out at once so that I could have 90 days sea time in 1967 to be eligible for the union's welfare benefits. These included hospitalization for the ensuing years for myself and Shirley, as my current insurance benefits in the Food Plan employment terminated with my severance from its payroll.

With all the faults that Paul Hall had as a human being and with all the derogatory epitaphs I may heap on him, I cannot deprive him of the place he built for himself in the political and economic life of this country. I shall admire him and will overlook much of the injustice and unfairness of his trade union regime for the simple fact that he started his career as a fighter against communism and ended it in no less a fervor. During the Second World War when this country was fighting on the side of Russia and it was popular for our leaders in government and labor to dine with and entertain Russian dignitaries, Paul Hall stood firm in his anti communism stance and to his dying day, I am sure he was fighting the avowed enemies of this country the communists. For this, I salute the tyrant!

Continue to next chapter...

(Introduction)

(Contents)

(Chap 1)

(Chap 2)

(Chap 3)

(Chap 4)

(Chap 5)

(Chap 6)

(Chap 7)

(Chap 8)

(Chap 9)

(Chap 10)

(Chap 11)

(Chap 12)

(Chap 13)

(Chap 14)

(Chap 15)

(Chap 16)

(Chap 17)

(Chap 18)

(Chap 19)

(Chap 20)

(Chap 21)

(Chap 22)

(Chap 23)

(Chap 24)

(Chap 25)

(Chap 26)

(Chap 27)

(Chap 28)

|