Chapter 24

THE END OF THE WAR

After the Philippines was liberated from the Japanese, stories began to surface of the atrocities committed against the Filipinos by the Japs during their occupation. No Filipino who read those stories could harbor anything but hatred towards the Japanese. As for me, I wished I could express that hatred in some physical way like hitting or kicking or even spitting on a Jap.

Then we heard of the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August and a week or so later we celebrated the defeat and surrender of Japan. We thought that we would soon be on our way home. The fact that we had signed on ship's articles for 12 months and that we had been away from home only a few months did not lessen our anticipation that we would soon be going home. This was not the case. We stayed in the Marshall Islands many more months and even overextended our 12 month articles to 13 months. The crew became restless. Tempers grew short. Amazingly, we had only two shipboard fights. However, three men were flown home for medical reasons and our third engineer, Jim Golson, drowned. These were our only casualties.

On our first visit to Tarawa, the evidence of the fierce battle between the Japanese and our forces was still fresh. Ruins of sunken boats and gun emplacements were everywhere. One can walk the perimeter of this atoll in less than 45 minutes, yet thousands of men lost their lives in the battle to wrest it from the Japanese.

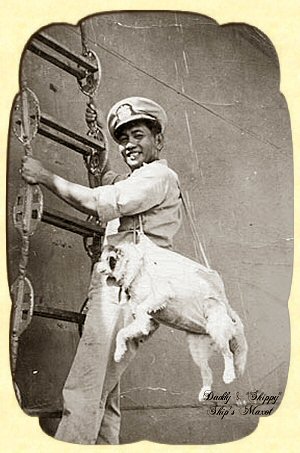

It was on Tarawa that we picked up a stray dog that had been left behind by the Marines when they left the atoll. At once, this half terrier mutt captured the crew's affection and he became the ship's mascot. We named him "Skippy".

As chief steward, I became Skippy's appointed guardian, but every member of the ship's crew and the Navy gun crew was his "parent" and protector. We devised a sling that strapped to one's shoulder where Skippy could ride. The sling, with Skippy tucked safely inside, could be worn when one of us climbed down the ship's side on a jacob's ladder. The movies were the only attractions we went ashore for and Skippy went with us on our shore leaves. He soon learned what liberty boat to take after the movies. We never had Skippy on a leash.

|

|

|

Felipe Morales Reyes and Skippy

|

Skippy became known to the servicemen in the different atolls we serviced as the "Wall Knot dog" and no one tried to re-adopt him. That is, until Guam. One day while we were docked in Guam, Skippy managed to slip ashore by the gangway. The captain instructed every man not on duty to go ashore to look for Skippy. The second day, he was found tied up in an Army barracks. Our crew, having no stomach for a confrontation with the Army, reported the fact to our captain. Captain Cage, the Chief, and I went to the C. O. and rescued Skippy without trouble. Skippy's unauthorized shore leave was terminated by his confinement in the spare cabin while we were in Guam.

Skippy was in the habit of jumping on the hatch which was closed most of the time, but one day he fell in the ship's hold while the deck crew was cleaning it. We thought he might die from his injuries. The ship's routine was disrupted. Every man came to my room every day to inquire about his condition. No member of our crew ever got as much attention as Skippy did when he was sick. Such was our mascot, Skippy.

Shortly after the Japanese surrendered, I met one of them. What would be my reaction? Would I hit him or spit in his face? I could do neither. The thought of Cato and Moto, my good friends at the Hall's who were so kind to me, and the sight of the man himself a former proud member of the Japanese Imperial Army, now so pathetic and humble turned my hatred to pity and compassion. This happened at Wake Island.

From Kwajalein we took a load of K Rations to Wake Island for the thousands of Japanese who were there when their government surrendered. We heard that they were on the verge of starvation. It was true. There were rumors, too, that the Americans the Japanese killed on the island left treasures of jewels and money and we decided to find some of it.

When the Japanese surrendered, a detachment of Marines was sent to Wake Island to hoist the American flag and occupy the Island. The Marines were billeted in tents in a small section of the island just a little over an acre. The rest of the island where the Japanese were was out of bounds for them. Of course, it was out of bounds for us, too. But Wake Island is a large island.

We decided on a landing party of six: three merchant crew and three Navy crew. We would be the first civilians to land on Wake Island since it had been retaken from the Japanese. The captain, chief mate and the Navy officer had pistols. The two Navy enlisted men and I were unarmed. I carried a large knapsack with our sandwiches, sardines, and candy. The enlisted men carried drinks. We used one of our lifeboats and landed at the opposite side of the island from where the Marines were billeted. Finally, I was to have my chance to hit or spit on a Japanese.

We saw a rusty, corrugated roof almost level with the ground and that's where we went my burning desire to hit or spit on some Jap never flickering. Until I met my Japanese. What I saw was a very thin, almost emaciated human being. My hate turned to compassion.

We walked further and came to a hospital set up in a roofed dugout. The doctor met us and in his smattering English he told us many of his patients lives were saved by the ending of the war and the reoccupation of the island by the Americans who brought and gave them food. Before we left, I emptied my sack of food and gave it to him for his patients. We asked him about the treasure. He just smiled and said he had heard of it too, but had never set eyes upon it.

Further on, we came upon an officer sitting outside of his tent cleaning a sextant. It was a beautiful instrument. Captain Cage was immediately drawn to it and told me to ask the man a high ranking Naval officer for it. He refused to give it to me, saying that it was now the property of the U. S. Government. Several men came to us. One gave me an old oriental fan. They wrote their names and addresses on it and invited us to visit with them in Japan if and when we went there. Again, we broached the subject of money and jewels with negative answers.

As we had given away what little food I was carrying, we decided to carry tea and canned goods the next day when we came again. This we did. Though we failed to find any money or jewels, the officer gave us the sextant when I told him I was a Japanese Filipino from Honolulu. We gave him all the food we had and he was very happy. He bowed a dozen times before we left. My party laughed at my story, but was glad I obtained the sextant. I gave it to our captain. Our treasure hunting was a failure.

1946 came and the Navy gun crew was taken off the ship. We thought then that we would surely return home soon, but the Navy kept us on the different small islands that were occupied by the Japanese. One of them was the island of Kushie, the first island where we saw women. We had to use our lifeboats to reach shore as the island like most of the Marshall Islands had no dock. I was enchanted with the beauty of the island and the goodness of the people.

Our crew, when they found out that there were women on the island, went ashore with beer and cigarettes: the articles of enticement the Americans used in Germany after the war. How wrong we were! They just laughed at us when we offered them beer and cigarettes. The women laughed most of all. None of the natives drank or smoked. The natives were simple but lovely people. They were all Christians and were led by King David, a man in his sixties. He was their preacher, their head man, and their doctor. When we met him, he reminded us of Jesus as depicted in storybooks. He wore flowing robes, walked with a staff, and went barefoot. His grandson was with him when we met him.

This is what we learned: A missionary couple from Boston came at the turn of the century and converted the people to Christianity. It prevailed to that day. There was no jail, no policeman, no crime. Everybody shared with each other. The place was abundant with wild fruit, coconuts, and breadfruit. I did not see any cultivated area. The crystal clear sea was full of fish. We asked King David to send us fruit to the ship and the next day a canoe full of coconuts, oranges, and bananas came alongside. The natives would not accept any money, so I gave them some bread and canned fruit. I heard that some of the Navy boys requested to live on the island. It was as near to paradise as any place I had ever seen.

After carrying materials to be used in a coming atomic bomb experiment to Bikini Island, we were ordered to return home. It was late April or early May when we started for home and we arrived in San Francisco on June 9, 1946.

Several of the men wanted to take Skippy home with them. To solve that problem, it was agreed that we would give him to Jim Golson's mother who lived in Prichard. Since I lived in Prichard, too, I became the instrument to accomplish that decision.

|

|

|

M/V Wall Knot manifest showing the captain on line 1 and Felipe on line 25.

|

A few days after I arrived home by air, Skippy arrived by train. The presentation of the Wall Knot's mascot to our late shipmate's mother received wide publicity in the Mobile papers.

Continue to next chapter...

(Introduction)

(Contents)

(Chap 1)

(Chap 2)

(Chap 3)

(Chap 4)

(Chap 5)

(Chap 6)

(Chap 7)

(Chap 8)

(Chap 9)

(Chap 10)

(Chap 11)

(Chap 12)

(Chap 13)

(Chap 14)

(Chap 15)

(Chap 16)

(Chap 17)

(Chap 18)

(Chap 19)

(Chap 20)

(Chap 21)

(Chap 22)

(Chap 23)

(Chap 24)

(Chap 25)

(Chap 26)

(Chap 27)

(Chap 28)

|